It had been six years, but once again Tanzania stood before us.

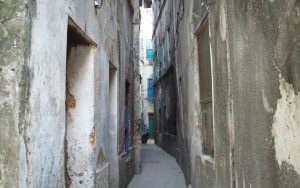

After spending nearly two days trapped on a plane, we arrived in the bustling city of Dar es Salaam. Within the past thirty years, Dar has grown from a sleepy Zaramo fishing village into a thriving tropical metropolis of over four million people and is East Africa’s second-busiest port and Tanzania’s commercial hub. It smelled muggy, hot, sweet, and dusty all at the same time.

We left the airport and met up with Moshi. He was exactly as I remembered him: serious, kind, and a man on a mission. We had spent over a year back in 2009 corresponding about the Cheku Water Project almost daily, but this was the first time seeing him since we met so many years ago. After a heartfelt reunion, we headed to the bus station to drop off our extra bags for Cheku. By this point in Zoe’s life, she was beginning to write more and more, and as any good mother would, I asked (sometimes bribed) her to keep a journal on this trip, so I’ll let her tell some of the story through her teenage eyes:

In the taxi, me, the two big boxes of presents (for the kids in Cheku), and Moshi were all crammed into the back of the cab. We were headed to the bus depot to drop these things off so that they arrived ahead of us in Kondoa. Driving down the streets of Dar is so nerve-racking. People are being honked at from every direction, pedestrians are walking an inch away from the car, and motorcycles are going too fast. Here in Tanzania, people honk to warn others that they’re coming, unlike Canada where we honk if we’re mad.

The next day at the hotel, while Zoe worked on her mountain of homework, Moshi and I sat for hours talking about the issues that we encountered on this complicated water project. It seemed crazy to have gathered so much knowledge and not apply it again, but with how stressful the Cheku Water Project had been, we both agreed that we would never tackle anything of that magnitude again.

We would focus instead on adding an environmental arm to Moshi’s already-established cultural tours.

Moshi grew up in the small village of Sori Tanzania, close to Cheku. His village was poor, and he left when he was sixteen to work in the nearby city of Arusha as a porter on Mount Kilimanjaro. Arusha was Tanzania’s gateway to the northern circuit of safari parks. The city sits below Mount Meru on the eastern branch of the Great Rift Valley. It’s where most tourists land before either heading out for a safari or climbing mount Kilimanjaro. For a few years, he climbed up and down the mountain carrying the luggage of tourists.

He learned the ins and outs of the thriving tourism business because almost everyone who climbed the mountain also wanted to do a safari in the famous Tanzanian parks. However, work as a porter was hard, so he decided to transition into the safari business. He went to school and learned about Tanzanian wildlife, and then through his contacts, he started working as a safari guide for some of the bigger companies. He did this in Arusha for a few years and then started doing some smaller tours on his own. Someone had written positively about him in Lonely Planet, and that’s how I found him. Over the years, he continued to work as a guide for different companies.

Later, after he got married and started a family of his own, he found that Arusha was a tough place to work, and he wanted to move his family back to a smaller community while still conducting tours, which is how his cultural tourism company came about. Kondoa was a good place for him to raise a family and tap into the handful of tourists that ventured into the region to see the UNESCO rock paintings. Plus—it was far less competitive. His cultural tours eventually evolved into a bigger initiative to bring the tourists in and around the area.

In hindsight, I imagine I wanted to be involved with his tours because it’s how I grew up, and it felt natural to build and grow projects. I often left school for a few weeks at a time to join my parents as they traveled around the world leading groups. In a way, having Zoe with me was like following in my parents’ footsteps, although that thought didn’t occur to me at the time.

Moshi and I talked all afternoon about ideas to develop his cultural tours that would integrate environmental projects and bring communities together. Plus, it was a way for Zoe and I to create our own adventure while we visited the different communities in the region.

That afternoon, Moshi left to do his own errands and Zoe and I decided to walk around. In Zoe’s letters, she switches between calling me mom, mommy, and Lara. Maybe she wanted to feel older and more professional, but she did drift back into mom and mommy at points. I think it was when she was feeling vulnerable.

We wanted to go to a coffee shop but apparently, coffee shops aren’t a regular thing here in Dar, so we were sent to a place that mostly served food. Me and Lara walked into this little blue open restaurant on the corner of the street called “A Tea Room”. I wasn’t that hungry and neither was Lara, but we went anyway. Inside, it had a bunch of scratched off no smoking signs and the tiny kitchen was decorated with fake flowers and trees. We got our food—which was pretty good—it was a deep fried samosas and pork. All the food I’ve eaten here so far has been completely deep fried, which is fine with me. Once we were done eating, we decided to get another drink, so Lara went to get it and came back with two cokes in her hand. We both realized after a few minutes that we’re supposed to sit down and order, but instead Lara had actually gone right into their kitchen and taken the drinks and food right out of the restaurant’s fridge! I was pretty embarrassed. We were these silly little tourists who were unaware and lost. After that incident, we decided to go back to the hotel and rest for a bit.

This was our first time being on our own, and being approached by people on the street caught me off guard. Even though they were only selling safaris, wares, and food, you have to be “on” here when you walk around. Simple things, like ordering at a restaurant or working a phone, are not obvious and routine tasks since everything is in Swahili, but we were humble and patient.

When Moshi returned, he was hungry and wanted to have dinner, and we didn’t have the heart to tell him that we’d already eaten, so we set off to have dinner—again.

Walking down the streets is even scarier than driving. Cars are brushing your arm while people are trying to sell you things. There are so many distractions. The place for dinner was the best food I’ve had since I got on the plane! It took a while to order because me and Lara are really slow, but it was ok because the food was heavenly. We could smell it from a mile away because it was being smoked right on the street. There were all types of things, from lamb to beef to kebabs to chicken wings. We tried to order something that looked really cool and yummy but the guy actually told us it was cow fat on a stick, so we ordered the lamb kebab instead (this time we sat down first). It came with fries and chapati bread. Afterward, I was stuffed so we went back to the hotel with our bellies completely full.

The next day, we hopped on a bus destined for Arusha, which was about 600 km (373 miles) away from Dar. From there, we would be heading out to Kondoa. Our plan was to visit the Tangire National Park in Mto wa Mbu to see some animals then and meet up with Richard, a friend of Moshi’s, who was also doing cultural tours and lived nearby. Richard was implementing environmental projects at the local village school, so Moshi wanted to stop by so that he could see some of his ideas and bring them back to villages in the Kondoa region.

Once we made it to Arusha, we met up with Abu, a close friend of Moshi’s, and then rented a vehicle—as well as a driver. At eight in the morning, we headed out to do our own little makeshift safari, passing through several villages until we made it to the park. Wildlife like zebras, elephants, and mpalas was abundant.

Today, we took a safari to Tangire National Park, and it was beautiful. I really love animals and we saw probably thousands of them. When we were passing the villages, there were kids on the side of the road. These kids were covered in dirt with ripped clothes and were selling fruit and any type of anything. They were probably seven years old. There was one little boy in particular whom me and mommy bought fruit off of (not sure what type). He was probably five or six and was completely alone. His hands and face were dusty from the road, and his little stomach had gotten big because he didn’t have enough food in his body. At that moment, I realized how lucky I am.

We made it to Richard’s village, Mto wa Mbu, after the sun had gone down. It lies within the East African Valley, about 120km (75 miles) from Arusha and was home to more than 18,000 thousand people and 120 different tribes. We met Richard and went out to a little place in the village for dinner. Since there were no street lamps, everything was dark, and we couldn’t really see much, but with flashlights in hand, we eventually found our way to the small restaurant.

We sat down under this little wooden patio that had five plastic chairs, a plastic table, a tablecloth, and a bright red lamp shining on top of us. The waitress came to the table with a bucket and a kettle. Me and Lara had no idea what she was doing, but Moshi explained to us that we had to wash our hands before we ate while she poured the water from the kettle on our hands. The chicken was local and was delicious but very chewy. The most exciting thing about the meal though was the ugali. We ate really late at night, so we couldn’t really see it, but ugali is this cornmeal dough that you dip into a stew and eat. The villagers eat it because it’s very filling, cheap, and easy to make. It came in a gigantic mound and we could not finish even half of it.

While getting our fingers gooey with ugali, we talked to Richard about his environmental work and his projects at the local school. We made plans to meet up the next morning to see some of what he was talking about, and then we went back to the hotel to get some sleep.

The hotel room is as small as my closet. There are two rickety and musty twin beds with furry, floral blankets on either side of the room. Outside, I can hear the bristles of a broom going back and forth along the sidewalk. The constant honks and chatter among the people create a soundscape. Here, everyone seems to be smiling. On the streets, there are rows and rows of people sitting with their plastic chairs and holding out the crazy assortment of things you can buy. There’s everything from watches to bananas, to t-shirts and phone cards. The people come to you yelling and trying to persuade you to come and buy their things. They’re so close you can feel their breath, and you can see the sweat dripping from their faces. The musty smell reminds me that I am not home.

We had breakfast with Richard, and then he took us to the elementary school where he taught. His main focus was replanting trees and teaching people how important they were to solving some of the water issues. He planted guava trees because they grew so quickly, and to make use of greywater, he planted sack gardens to grow vegetables.

The village that Richard worked in suffered due to its proximity to the safari parks. There was actually a large hotel just outside the village that used up most of the water for its guests, leaving the villagers with next to nothing. Even the reservoir tank at the elementary school was empty. The cost of the land had increased by so much that only bigger businesses were able to afford anything, so they scooped up the best pieces of land and took all the water.

In a week, we planned to meet Richard in Kondoa (the district where Cheku, Iyoli, and many other small villages were). He had agreed to speak with the elders of these villages about implementing some of the projects he had been working on in order to help with the water situation. With any luck, it wouldn’t be too long before we were putting some of these projects into motion.