One day, I was having dinner with Amina and Aisha, and they brought me a plate of small, dried fish they had cooked.

I used Google Translate on my phone to figure out that they were probably anchovies (daga), but Google wasn’t always accurate. Nevertheless, they were fish, and typically I have to leave the room whenever there’s fish, or anything that smells like fish. Let it be a testament to how much I adored Aimina and Aisha because I not only stayed in the room, I also ate the heaping mountain of fish.While we were eating, the girls showed me a picture of this huge, pumped-up guy on their phone. In my broken Swahili, I asked “anapenda mvulana kubwa,” which I hoped meant something along the lines of, “you like big muscles?” But I’m not quite sure how they interpreted it. They did giggle, though, and start acting out an elaborate skit of pumping iron. They were both so young and fun and weren’t really that much older than Zoe, but their lives had been anything but easy. Amina was twenty-one, and her son was six, so she probably had him when she was about fifteen. By many standards, fifteen was still a baby, and though it was illegal to marry someone under eighteen, it obviously still happened. What I have figured out over time is that there are other ways to communicate with people outside of language. Many mornings, I woke up early and would sit out in the kitchen, which not only forced me to speak Swahili since no one spoke English, it also made me improvise in other ways. I’d often use hand gestures, and when I’d imitate an animal or bug, people would laugh at how silly I was being. They were laughing at me, but in a good way—and it really saved time in getting my point across.

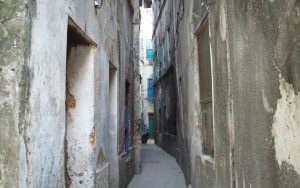

After my time in the kitchen, I would grab a cup of coffee and sit out on the porch. Usually, either Aisha, Oliva, or Amina would join me. Anyone who walked by often knew one of them and would say hello. One time, the woman next door came over and asked how many children I had (“Watoto wengi?”). It took me a while to figure out what she was saying, and after telling her I had one, I tried telling her Zoe’s age and had to count up to seventeen. That took a long time and the numbers four and eight (nne and nane) always caused me to panic.

Greetings also made me panic. I think it’s because they are almost an art form. An average of two to three question/answer exchanges is normal between strangers, and there are even more if you actually know the person. A casual greeting such as “Niaje” or “Vipi?” calls for an equally casual answer, and there are so many words to choose from. The respectful “Shikamoo? Marahaba” is a way to address an older person. A typical early morning greeting could be “Umeamkaje?” (How did you wake up?), and to that, you answer “Salama!” or “Vyema!”

One day, Moshi and I were sitting on the porch hotel working when an older man came up to me and said “How are you?” My brain went blank as I tried to respond in Swahili. I couldn’t think of anything, so Moshi turned to me and said that I should say “I am fine,” which I repeated back to the old man. Then the man turned to ask Moshi if I spoke any English at all. My confused and complicated brain didn’t register that he was actually speaking to me IN ENGLISH, so I panicked as I do when I’m trying to speak Swahili and searching for a response. Trying to speak Swahili is hard and embarrassing at times.

The Wi-Fi at the hotel not only allowed me to easily stay in contact with Zoe and Loc back in Canada, it also let me look up words on my phone, which made it much easier to converse. On occasion, I’d pull up a translation on my phone and then pass it around. These situations allowed me to make statements that would otherwise be impossible, like “Canadians do not like being mistaken for Americans. We love each other but we have our own identity.”

Life at the hotel grew familiar, and in the six days since my first meeting with Ikaji, I began to recognize the simple things, like the fact that I needed to cut my bangs because they kept getting into my eyes. I borrowed a pair of scissors, but they were dull, and the hack-job left my bangs uneven—I know, first world problems. I looked ridiculous but felt like I was exactly where I needed to be, so I just ignored it and ventured forth.