My family went their separate ways and Zoe, Loc, and I hit the roads of Tanzania. It was raw and wild. If you moved outside of the paved roads of the northern safari circuit, you’ll see the real Tanzania—thirsty but full of life.

It was in Tanzania where I met Moshi Changai.

Moshi was a guide that I met on the internet through the Lonely Planet website to take Loc, Zoe, and I to the Ngorongoro Crater, Tarangire, and Lake Manyara National Park in Tanzania. They are from the Irangi tribe and escaped the poverty of their tiny village through the tourism industry and know everything there is to know about African animals and the environment.

Moshi would end up becoming a big part of my life in the years that followed.

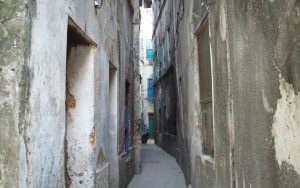

After visiting the typical Tanzania game parks, we headed to a small village called Sori, where Moshi and Chudi had grown up. On the way, we passed countless shanty towns where rickety old buildings looked as though they would fall down if someone sneezed. As we drove, I wondered about the people of these villages. We saw young boys crossing the road with a herd of cattle and women walking with bright yellow buckets on their heads. Children yelled “muzungu” at our car as we passed.

When we finally arrived, we were greeted by three of the village women. They smeared a green mixture of goat remains, spit, and bark on our foreheads. It was a gesture of peace they did for visitors or for someone who had been away for a long time. Their native language was Irangi, and the only words I could speak were, “Hello, nice to meet you.” I kept repeating them over and over again until Zoe broke the ice by bouncing up and down while chasing a goat, which made the villagers laugh.

On the way to Sori, we had stopped at the Kondoa market to buy head coverings out of respect for the predominantly Muslim villagers, but after thirty minutes of the heat, I couldn’t bear it any longer, so I took the scarf off.

Afterward, Moshi introduced us to the woman who raised him and took us into the mud hut where he grew up. He sometimes had to share his sleeping area with newborn goats, but it was better than allowing them to be eaten by the lions, and the tiny window on the far walls let only a sliver of light through.

Loc and I then walked with the villagers to where they collected water from a well while Zoe rode on a donkey cart. The trip took over twenty minutes in the sweltering sun, and once we arrived, over fifty people were waiting in line. The loud diesel powered pump gave off unbearable fumes, Families visited this pump two or three times a day, and often, they send their daughters, who might be five or younger. These children would carry the buckets on their heads back home for another twenty minutes in the hot sun, but the well and pump made this village one of the luckier ones. In other areas, villagers have to travel over ten kilometers (about six miles) to collect water from what was basically a puddle. Reality of life without water is grueling, a fact that was all too common.

That image stayed with me.

Our time in Tanzania, and Sori in particular, matured Zoe and she grew to understand the value of a hot shower, a full meal, a soft bed, and good drinking water at only seven years old.