[fusion_builder_container hundred_percent=”no” equal_height_columns=”no” menu_anchor=”” hide_on_mobile=”small-visibility,medium-visibility,large-visibility” class=”” id=”” background_color=”” background_image=”” background_position=”center center” background_repeat=”no-repeat” fade=”no” background_parallax=”none” parallax_speed=”0.3″ video_mp4=”” video_webm=”” video_ogv=”” video_url=”” video_aspect_ratio=”16:9″ video_loop=”yes” video_mute=”yes” overlay_color=”” video_preview_image=”” border_size=”” border_color=”” border_style=”solid” padding_top=”” padding_bottom=”” padding_left=”” padding_right=”” admin_toggled=”no” admin_label=”After spending so long in Africa”][fusion_builder_row][fusion_builder_column type=”1_1″ layout=”1_1″ background_position=”left top” background_color=”” border_size=”” border_color=”” border_style=”solid” border_position=”all” spacing=”yes” background_image=”” background_repeat=”no-repeat” padding_top=”” padding_right=”” padding_bottom=”” padding_left=”” margin_top=”0px” margin_bottom=”0px” class=”” id=”” animation_type=”” animation_speed=”0.3″ animation_direction=”left” hide_on_mobile=”small-visibility,medium-visibility,large-visibility” center_content=”no” last=”no” min_height=”” hover_type=”none” link=””][fusion_text columns=”” column_min_width=”” column_spacing=”” rule_style=”default” rule_size=”” rule_color=”” hide_on_mobile=”small-visibility,medium-visibility,large-visibility” class=”” id=”” animation_type=”” animation_direction=”left” animation_speed=”0.3″ animation_offset=””]

After spending so long in Africa, the time had come to return to Vancouver. In the fall of 2007, Zoe went back to Queen Victoria School on Vancouver’s east side.

Her teacher, Perry Buchan, heard bits and pieces about our trip from her seven-year-old perspective, which inspired him to integrate a section on water into the school’s curriculum. It takes a special kind of person to imagine a project and then make it happen. That is Perry.

And so, with Perry helming the efforts, the Cheku Water Project began. At first, helping an African village halfway around the world was a hard sell to many members of the community, but with Perry’s help, the project eventually evolved into a school-wide initiative. The teachers at Queen Victoria developed curriculum about water related issues, both local and global. What resonated with them the most was the situation in developing countries like Tanzania.

The students wanted to know more about this world that was so far removed from life in Vancouver. With Moshi’s help, they began writing letters to pen pals in Cheku, but soon, the students wanted to actually do something to help the village—that something turned into digging a well, but that required money, and the creation of a borehole.

Naively, we went straight into raising funds to build the well.

The school hosted a walk for water so that the kids could feel, if only for a day, what it was like to have to carry water, which had a huge impact. One of the other things the school did to raise funds, and to help the community understand what the kids were doing, was to have them write and perform a play about water in general—and specifically how the children in the village of Cheku lived and dealt with their water issues. Artists-in-residence, staff and community members worked with the children to help develop an original script, original music, sets, props and costumes. In this way the learning of the children was transformed into a theatre piece that would create awareness and support for the project.

[/fusion_text][/fusion_builder_column][/fusion_builder_row][/fusion_builder_container][fusion_global id=”18013″][fusion_builder_container hundred_percent=”no” equal_height_columns=”no” menu_anchor=”” hide_on_mobile=”small-visibility,medium-visibility,large-visibility” class=”” id=”” background_color=”” background_image=”” background_position=”center center” background_repeat=”no-repeat” fade=”no” background_parallax=”none” parallax_speed=”0.3″ video_mp4=”” video_webm=”” video_ogv=”” video_url=”” video_aspect_ratio=”16:9″ video_loop=”yes” video_mute=”yes” overlay_color=”” video_preview_image=”” border_size=”” border_color=”” border_style=”solid” padding_top=”” padding_bottom=”” padding_left=”” padding_right=”” admin_toggled=”no” admin_label=”It took well over a year”][fusion_builder_row][fusion_builder_column type=”1_1″ layout=”1_1″ background_position=”left top” background_color=”” border_size=”” border_color=”” border_style=”solid” border_position=”all” spacing=”yes” background_image=”” background_repeat=”no-repeat” padding_top=”” padding_right=”” padding_bottom=”” padding_left=”” margin_top=”0px” margin_bottom=”0px” class=”” id=”” animation_type=”” animation_speed=”0.3″ animation_direction=”left” hide_on_mobile=”small-visibility,medium-visibility,large-visibility” center_content=”no” last=”no” min_height=”” hover_type=”none” link=””][fusion_text columns=”” column_min_width=”” column_spacing=”” rule_style=”default” rule_size=”” rule_color=”” hide_on_mobile=”small-visibility,medium-visibility,large-visibility” class=”” id=”” animation_type=”” animation_direction=”left” animation_speed=”0.3″ animation_offset=””]

It took well over a year, but the small community eventually raised about $20,000. From there, plans started to come together quickly. With the help of an engineer named Dominic, we formed a small water committee at the school. I had spoken to a woman from Engineers Without Borders, Erin, who had worked on a similar project in Tanzania, and she pointed us toward a few different companies, and we got their quotes. Then together with Moshi as project manager, we chose a driller who we all thought would do a good job. We conducted a few surveys and narrowed our chances of finding water down to three sites, and while the location we picked was our best bet, there was always the possibility of spending $20,000 and finding nothing.

On March 24th, 2009, nearly two years after we came back from Uganda, drilling began, but it was slow going with frequent obstacles. First, the rig’s clutch plate had a problem, so it took a few days just to get the machine into the village. Then the gearbox transmission as well as the main hydraulic pumping system both had problems. Mr. Wilson and Mr. Toni, the lead drillers, went back to Dar es Salaam to fix it, but they ended up travelling to India to buy a new part (to this day, I still have no idea why they didn’t just have it sent to Dar). While this was going on, I slept with my phone under my pillow waiting in case the project needed help.

[/fusion_text][/fusion_builder_column][/fusion_builder_row][/fusion_builder_container][fusion_builder_container hundred_percent=”no” equal_height_columns=”no” menu_anchor=”” hide_on_mobile=”small-visibility,medium-visibility,large-visibility” class=”” id=”” background_color=”” background_image=”” background_position=”center center” background_repeat=”no-repeat” fade=”no” background_parallax=”none” parallax_speed=”0.3″ video_mp4=”” video_webm=”” video_ogv=”” video_url=”” video_aspect_ratio=”16:9″ video_loop=”yes” video_mute=”yes” overlay_color=”” video_preview_image=”” border_size=”” border_color=”” border_style=”solid” padding_top=”” padding_bottom=”” padding_left=”” padding_right=”” admin_toggled=”no” admin_label=”During this time”][fusion_builder_row][fusion_builder_column type=”1_1″ layout=”1_1″ background_position=”left top” background_color=”” border_size=”” border_color=”” border_style=”solid” border_position=”all” spacing=”yes” background_image=”” background_repeat=”no-repeat” padding_top=”” padding_right=”” padding_bottom=”” padding_left=”” margin_top=”0px” margin_bottom=”0px” class=”” id=”” animation_type=”” animation_speed=”0.3″ animation_direction=”left” hide_on_mobile=”small-visibility,medium-visibility,large-visibility” center_content=”no” last=”no” min_height=”” hover_type=”none” link=””][fusion_text columns=”” column_min_width=”” column_spacing=”” rule_style=”default” rule_size=”” rule_color=”” hide_on_mobile=”small-visibility,medium-visibility,large-visibility” class=”” id=”” animation_type=”” animation_direction=”left” animation_speed=”0.3″ animation_offset=””]

During this time, Moshi sent frequent emails, edited for clarity, to keep us all up to date on what was happening.

Mr. Wilson and Mr. Toni left to Dar to try and fix a problem with the rig, and once that’s done, I’m hoping that drilling will start, and that everyone will be happy. It worries me that we keep having problems with the rig since we are depending on it to make everyone’s dream come true. I had Mr. Dominic (our engineer in Canada) ask Mr. Wilson to confirm that if we keep having trouble with this rig that he will send us another one and not continue fixing this one.

That rig did end up needing to be replaced with a less faulty one, and Moshi kept the pressure high until that happened, and as a matter of fact, the old one still sits rusting in Cheku.

Deeper and deeper they dug with the new rig in search of water.

The drilling went well. The villagers who visited were happy, and the drilling excited everyone. We ran out of fuel, but if we hadn’t, we would have been able to drill down deeper.

In hindsight, as I read through these letters—with the water project behind us—I realize that work in Tanzania is crazy and inefficient. Companies will run out of gas and that’s it; the project would stop for a few days. Thinking about it still stresses me out.

We successfully drilled again. With the borehole as deep as it was, Mr. Beda, Joseph, and I had a discussion about the PVC installation that needed to be applied.

The PVC piping was intended to keep the well from collapsing in on itself once it was dug. Many drillers actually cheated their clients and skipped this part of the process. Moshi put a lot of effort in keeping this project running and to make sure everything was done, and done well. He kept breathing down everyone’s necks and watching their every move. He measured and double checked everything.

Mr. Bago (the water engineering consultant), is working in the Mbeya Region in the Southern Highlands of Tanzania. Although he wishes he could be here, it is not possible. I call him every day to talk, and he advised me to watch that the PVC installation is done properly.

Anytime Moshi needed Mr. Bago’s expertise, he would call him and then direct the drillers. Also, remember that Moshi is from the small neighbouring village of Sori. He had no schooling and taught himself everything, and by the end, he knew as much as the engineers.

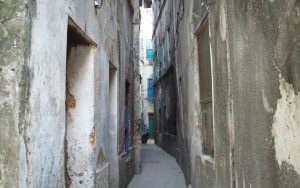

Today, we began cleaning the well now that the PVC had been successfully installed. The Cheku villagers who visited the site were happy because they witnessed the water with their own eyes. In dry seasons, like today, women and young children must wake up in the middle of the night and walk far to collect water, which sometimes they wouldn’t even find. The community visited the project site and couldn’t believe that there was water. Most of them brought their cattle to drink and collected water for washing at home. They won’t forget this.

Seven months later, on October 24th, 2009, the well was all but complete. We verified that the water was safe to drink without serious purification efforts, but we still needed to get the water to the surface, and that required a high-quality pump.

Important Borehole specifications:

Well casing bore hole size = 5″

Total well depth = 78m

Static Water Level (static head or depth to water) = 25m

Refresh rate = 2000L/hr (8-9gpm)

Location: 05.09490-S Latitude, 35.86630-E Longitude

An electric pump, however, wasn’t cheap, and by now, we were all but out of money. The drilling team left, and the daunting task remained of raising more funds, something that might not have been an issue if we had help from an organization that knew the complexity of building a well, but we were making up this project as we went along.

An electric pump was the only real solution to a borehole of that depth and we had to wait for the money.

As the weeks went on, the villagers had to suffer with a well that they couldn’t even use while I woke up wondering how the hell we were going to find another $20,000. I Googled “pumps” and “solar” and called every single company that had anything to do with water.

I must have called over thirty different companies, and they all thought I was crazy, but the experience gave me a thick skin. I learned how to talk about the project with others and that a “no” simply meant that I needed to look harder.

Then, in January of 2011, we finally got a stroke of luck when the Canadian International Development Agency (CIDA) offered us one of their very last grants. For over a year, the well wasn’t even functional, and within just a month, we had a working, solar-powered well and water storage in the middle of a small village in Tanzania. All it takes is money.

To officially handover the project, Moshi held a formal village meeting in Cheku that established that everyone would be responsible for the water project. They agreed that they would create a local government specifically for water issues and charge an affordable amount for fetching water and bringing cattle to the well. The fees would go into a bank account and be used for future maintenance of the well.

And so, for nearly two years after that, I drank my glass of water nightly while sitting on the porch with Loc, and I thought about that well. It wouldn’t truly be real until I could stand in front of it and see it with my own two eyes. So, once again in 2013—over six years since our trip to Uganda—I took Zoe, who was now fifteen, out of school, and we traveled to Tanzania to see that well.

[/fusion_text][/fusion_builder_column][/fusion_builder_row][/fusion_builder_container]