A few days after the water surveys, we made plans to head back into Iyoli, and with the help of our driver Issa, we packed the car with computer equipment, a generator, and people—Moshi, Baraka, Habiba, and now Evelyn.

She was friends with Moshi’s wife and could speak English. Since her goal was to become a journalist, she was going to help film all of the interviews. We were a ragtag team of enthusiastic people ready to roll and screen the work that Starthcona had created for their sister school.

Moshi greeted the kids from the class, the elders, and the village chairman. They had all come to the school to be a part of the proceedings. He then spoke to the twenty kids from the storytelling club, thanking them for being a part of the program and saying how important it was to record these stories. Afterward, Baraka stood up and read three of the stories from the Strathcona book that had all been translated into Swahili.

After lunch, we finally watched the videos that the Strathcona kids had created with a projector that I’d brought along and set up.

The kids in the storytelling club watched the Canadian kids greet and introduce themselves, and then, at the end of the song, one of the Strathcona kids wrote, “children of Iyoli, we love you,” and they understood that there were kids on the other side of the world who cared.

At the end of the day, we set up the projector in the village center and invited everyone from the community to come and watch these videos in addition a Swahili movie that Moshi had picked out. I couldn’t understand a word, and the projection was tilted and blurry, but it seemed to be about some grown man who kept getting into trouble and was repeatedly sent back to primary school. The crowd of 200 people seemed to find it hilarious, though.

As night fell, and the stars came out, Baraka fell asleep on my lap with her fingers twisted through my hair as the generator softly hummed in the distance.

On our way back to the hotel, I thought to myself that the night had been my idea of perfection.

Over the next week Moshi, Evelyn, Habiba, Baraka, and I went back and forth to Iyoli and helped to film the interviews with the kids in the storytelling club.

The students were shy at first, but Evelyn flexed her journalism muscles and helped to make them relaxed and silly. At one point, she asked me to leave because my presence made it more formal, but when it was just them and Evelyn, they were funny and more authentic. At the end of each day, she came to the hotel, and we would translate the interviews into English.

Issa was around while we were translating, and he was well aware of how much I loved coffee and how much I hated Nescafe, so he would constantly fill my tiny cup with the big thermos filled with Tanzanian coffee that he had brought from Kondoa town.

After they finished their interviews, the kids would break out into song, and I’d join them in my own silly way to try to make them all laugh. By the end of the week, we were all more comfortable around each other. Each interview made the kids more and more excited to be asked questions, and when they saw the videos of themselves being played back, they erupted into even more laughter. Everyone was having fun.

On the last day of filming, we went with the kids to collect water from a river bed. The red dust of Tanzania had settled onto my skin, and my hair was half-braided and full of sand because Baraka only had the chance to finish one side, but I owned the look.

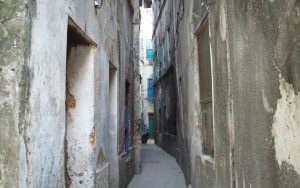

The river had dried up, and families, mostly women and girls—but boys and men too—had to dig holes to reach the underground water. As the dry season went on, the holes became deeper and deeper until there was no more water left to find. Then they had to walk farther to the larger Bubu river. When things got really bad, some families had to spend up to eight hours a day collecting water.

Many people have strong opinions about foreign aid and what should or shouldn’t be done, but when you stand together with kids, and mothers, and fathers and cows and goats, it’s not about politics and academia and theories, it’s about friends and their survival. At the end of the day, these kids were just like any other kids in the world. They were playful, curious, and at times even a bit naughty. And if you took a step back and thought about the big picture, so many of the hardships that people on the other side of the world face were directly caused by changes in the climate driven by people in the West.

One the way home, it finally started to rain. The dust settled and I could smell the fresh, clean air, and it reminded me just how important this was to Iyoli village.