Many years ago I traveled to Africa for the first time. Uganda.

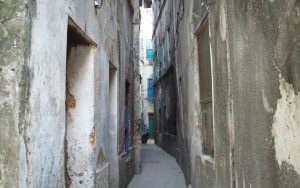

Being in Kalagala was like living in another world. The soil was a deep and rusty red that stuck to our skin. The dust in the air always left a film on everything and no matter how hard we scrubbed, nothing came clean.

The days were so bright and sunny that our goal was to find a tree for shade to save us from the heat. Nights, on the other hand, became so dark that all we wanted to do was to find light. In the darkness, we commonly heard bats, crickets, birds, and—if we were lucky—the distant sound of singing from the girl’s dormitory.

With the intermittent electricity, we were lucky to get an hour of illumination, let alone power for anything else in the countryside. With no pre-packaged entertainment, we often passed the time with song or dance.

The date was February 29, 2004, a Sunday. My mom and dad were in Guatemala leading a tour group of thirty people while staying at a bed and breakfast hacienda. The owner of that establishment also had a cabin on the Pacific Ocean about an hour and a half away, so on that February day, they were going to be spending time at the beach.

When someone dies tragically, you grab onto anything that lets you remember who they were. I guess that’s why there are so many benches in parks or plaques on buildings. Choosing to go to Uganda was almost random. A guy my dad knew, Maweji, was a Ugandan living in Winnipeg. Maweji had a school in his home village of Kalagala that he went back and forth to help. We learned that the school needed a computer lab, and that was just a good a reason as any, but it wasn’t why we went. We didn’t go for a sense of “doing good,” we were just looking for a place to go together, something to hold onto.

My mom was the last one onto a crowded van, so she sat on the floor behind the front passenger seat. My dad told me that she wouldn’t stop showing off pictures of her three daughters. She was talking about us and telling funny stories, using tall tales of her daughter’s escapades to keep the passengers entertained.

Before leaving Canada for Uganda, my partner Loc and my daughter Zoe, who was seven-years-old at the time spent a year collecting computers and money. We sold our car, rented out our house, and saved every penny so that we could spend some time here with the students, living with them in Kalagala. And so, makeshift plans made, my partner Loc, daughter Zoe, my father (Irv), as well as my two sisters (Kirsten and Rebecca), their partners (Wayne and Bryan), and my nephew (Justin), all packed our bags.

Their journey to the water was important because of the tragedy that was about to happen. It was difficult to go from the ocean to the village and back. By now, everyone had changed into swimwear back at the cabin. The waves were high. About an hour later, my mom walked along the shoreline with one of the passengers. They noticed the strength of the undertow and decided to warn the other passengers who were in two groups, a large one and a small one.

Plans for the computer lab continued, but there were some electrical issues at the school we needed to handle first. The last electrician had forgotten (or neglected) to hook up the ground wires, and there was a short circuit that needed fixing. So one day, we went into Mpigi, a fifteen-minute walk from the school, to meet with the local electrician at a restaurant. One of the teachers, Hassan, went with us, and on the way, we stopped to see his grandmother, who gave us some papaya and avocados from her trees. We left a while later to continue our journey into town.

One of my mom’s friends headed the smaller group while she continued along the water’s edge.

We arrived at the restaurant and waited half an hour for the electrician to show. When that didn’t happen, Hassan suggested walking up the road to his shop. Someone there told us that he was actually in Kampala and gave a phone number. We left the shop and started to cross over to the local phone, but we were first distracted by a man selling grasshoppers. In the West, these insects are used to feed pet snakes, but here, the kids like to eat them fried. So we bought the entire bag for the school.

Finally, we made it to the phone. Hassan called the electrician, and they made plans to pick up the supplies and begin work the next day.

My mother came to a place where seven people were swimming in the water. She waved them out. As they came out of the water, one woman, Urma, screamed for help. She had lost her footing. For years, I blamed her. It’s hard not to look for someone to blame.

On the way home, we stopped at the local bar for a beer before returning to the school. The grasshoppers, never ones to cooperate, were struggling to get out of the bag, so we tied it at the top, but since we didn’t get back to the school for nearly four hours—and the African sun is hot—many of them suffocated, and we arrived with a bag of half dead grasshoppers, but since they were about to be fried anyway, that didn’t matter too much. And we had news that the electrician would be there in the morning. Mission accomplished.

My mom waded in and stretched out her hand to help the woman in trouble, but in so doing, she also lost her footing, and the undertow pulled them into a stream of water, first back and forth along the shoreline, and then into a stream straight out into the ocean. By this time, the people on shore were frantic. A neighbor in the next cabin, a doctor—and two Spanish men—got into a boat and tried pushing it out, but the waves were big and it was difficult. Finally, they got beyond the waves’ breaking point and headed out to where they could see two heads bobbing in the water.

We gave the grasshoppers to the cook and told her that we wanted to help prepare them. Hundreds of grasshoppers needed their legs, antennae, and wings plucked. Many were still alive and would wiggle between our fingers trying to escape, but the dead ones were much more cooperative. There was enough oil in their bellies that we just threw them into a pan and they fried in their own juices. When they were done, the cook came and put a big bowl in front of us. I closed my eyes and ate them, forgetting that they were insects. They tasted kind of like chips.

Time moved slowly.

Learning often happened at night when the lanterns were lit and there was nothing to do but sit around and chat, sing, and dance. The kids would often congregate to one spot and start singing one of their Ugandan songs, and then everybody would join in together. It was powerful and moving to hear thirty voices together. The girls loved to show off their dance moves and Zoe, who was seven at the time, joined right in. Zoe has even shown them a few moves of her own.

My mom and Urma were holding onto each other with one arm while treading water with the other.

“There’s the boat!” my mother shouted, and as it approached, Urma disentangled herself from my mother and swam to the boat to get in. She left her in the middle of the ocean—alone.

We had a recording party one evening after we had dealt with the electrical issues. The music echoed through the night like a kind of call, reassurance that we existed. One student in particular, Rogers, wrote songs that spoke of his home and family. His parents died and he took care of himself and his brother by digging ditches when he was not in school. Another, Abdule, sang one of the songs by the famous Ugandan artist, Bobby Wine. Abdule’s soft voice floated effortlessly through the air and still resonates with me years later.

When she was being pulled into the boat by the men, they looked for my mother and saw her lying face down in the water. They eased the boat closer but had a difficult time pulling her up. Once they did, they were unable to lay her flat to give her artificial respiration because of seats bolted to the floor of the boat.

They headed for shore and landed. Several of the passengers were nurses, and they took turns trying to no avail to resuscitate my mother.

Eventually, we finished work on the computer lab and to celebrate, we had a party for its opening. Over 400 hundred people attended, including parents as well as other people from the village. Many of them came only for the food—which we provided a lot of—but the kids put together a great show. There was a play about child labor, a traditional circumcision dance, a poem, and lots and lots of drumming, singing, and dancing.

Wally Schmidt, my mom’s boss, called for an ambulance from the village of Coatepeque about half an hour’s drive away from our current village with the dock. When the ambulance arrived, two men took a stretcher and made the arduous journey to the cabin dock, up the hill past the cabin and down the other side where the people were gathered around my mother beside the water. They put her on the stretcher and went back the way they had come to the waiting ambulance.

Two passenger nurses went with my mom in the ambulance. They said the ambulance bounced from side to side as it careened through groups of people on the way to Coatepeque.

If audience members liked what they saw, they would throw money or candy onto the stage. If a person wanted to give something to a specific performer, they stepped right onstage and handed it to them, and then they joined right in with the performance.

My mother, Diane Kroeker, was pronounced dead upon arrival at the Coatepeque hospital.

Together with my family, we placed a plaque on the building that said, “in memory of Diane Kroeker,” and it felt good to see my mother’s name. Seeing the hardship of some of the students made me feel less sorry for myself. My experiences in Kalagala helped me to see something more than my mother’s drowning face whenever I thought of her.

And I will remember her.

A few students, in particular, will always stay in my mind. Rogers, Caro, Ashanti, Ham Dam, Moses, Crispin, Tabatha, Maureen, Stella, Sara, Olive, Barbara, Violet, Brandon and Madina who all made me feel more than welcome, and when we left, I felt as though they would also carry memories of me

Everyone wants to be remembered.