As I looked out the window on our overfilled bus bound for Kondoa, I saw field after field of dried up corn, more painful evidence of climate change.

The late rains had caused the crops to dry and prices to rise dramatically, making the corn—or maize— unaffordable for much of the population. Many families, including Moshi’s, managed by borrowing from a friend, or if someone could spare, they would lend out the little bit of money they did have to someone who was worse off.

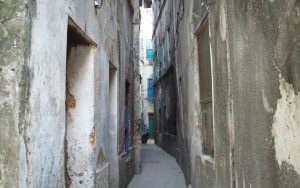

Moshi dropped me off at the Kondoa Climax Hotel and then went home to catch up with his wife and kids. I unpacked my bags and made the little pink room home. It had a double bed and a door that opened up onto a shared courtyard. I soon met three of the girls who worked at the hotel, Amina, Aisha, and Oliva, and I immediately liked them. I was the only guest, and because no one spoke English, they had plenty of time to teach me some simple Swahili.

Language is what connects us, but it’s also what makes it nerve wracking to be in another country if you can’t speak it, especially in a country with huge differences in dress, religion, and socio-economic situations. Not being able to speak makes people seem scary, but the minute you share a laugh, you move from stranger to friend and it invites people to talk to you.

While learning Swahili, my favourite phrase was “pili pili ho ho,” which means green pepper, but I thought it sounded more like a dance move—and the girls loved to dance. Sometimes one of them would flip over the yellow washing bucket and drum out a beat while saying these words and dancing. The girls were all in their early twenties and full of energy, so they laughed a lot—although sometimes I couldn’t tell if they were laughing at me or with me, but either way, I was learning bit by bit and, sometimes I danced right along with them.

Moshi and I spent the next few days working hard to write tour itineraries for the company while sitting on the porch. One day, as we were working, the aunt of the owner came by and threw the familiar traditional blessing on the house. She flicked a white mixture at our feet and all along the length of the porch while chanting ululations—the same ones that Zoe and I had experienced during our previous trip.

The time finally came for me to meet Ikaji. He was a smart guy who worked at the local hospital, but from the moment we met, something just didn’t click, and I felt awkward and uncomfortable. He was wearing a suit and tie, and since I didn’t think to dress up, I was wearing jeans and a long sleeve shirt. As he looked me over, I could feel the judgement in his eyes, but I wanted to make progress, so I just kept talking and making plans. Language barriers were difficult enough, but it hadn’t occurred to me until this trip that cultural differences presented an entirely new set of challenges. In Vancouver, people liked my creativity, but in Kondoa, Ikaji had no idea how to read how I presented myself, and I had no idea how to read his shiny shoes and suit; I wasn’t used to the business etiquette of Tanzania.