Like sardines in a can, we crammed onto a bus bound for Kondoa. We found our seats as more and more people boarded, and then—just when I thought we were as full as can be—they let a few more people on.

We woke up to the sound of roosters and made our way to the bus station. A blue carpeted ceiling with little splatters of neon colours gave the bus a disco type of feeling. There were fake plastic green leaves hanging from the front that had begun to slowly fall off. The thick warm smell of gasoline filled your lungs as you squished around to find the right seat. I noticed more and more people coming into the bus one at a time. Lots of mothers with adorable little babies wrapped in african shawls as well as very old men who could barely make it up the stairs. The people just kept coming and coming. About 50-75 people were standing or sitting in the middle of the bus with no seat. They pushed and shoved their way through. In the background you could hear a few arguments in Swahili.

When the bus finally started moving with a loud start of the engine, people became antsy. Supposedly, it was a two-hour bus ride, but we all knew better. Half an hour passed when all of a sudden, all the people standing or sitting in the middle ran off the bus and hopped into a tiny yellow minivan. It was almost like a clown car because of how squished in they are. Moshi told us that they were doing this because up ahead there were traffic control cops. I guess they didn’t check the smaller cars stuffed with people, only the big big busses. I was really glad that we were in a seat. I don’t think I would be able to do that. We drove up past the traffic police and an exchange was made. A couple of miles later, the yellow van appeared and the people hopped right back in. I thought that it was pretty funny.

We sat like this for over three hours.

The bus ride was long and uncomfortable because there were no breaks. Near the end, it felt like all the babies were crying at the same time. You could feel the people becoming more and more impatient and so was I.

Our trip had taken slightly longer than anticipated because we had to stop at one of the villages to let Zoe use the restroom, but finally, we arrived in Kondoa.

Walking off the bus is always confusing. First it’s like a huge blast of heat hitting you directly in the face, and second, there are people all around you trying to entice you to take their taxi. Moshi always knows the best people to pick, so we headed into the cab and to our new hotel.

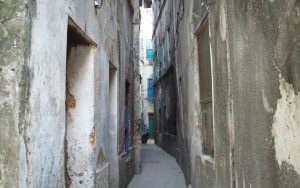

Dar es Salaam may have been a foreign city, but it was also a tourist spot, so you could acclimate to the environment easily enough. Kondoa was different because you were closer to the real hustle and bustle of daily life. Imagine the sound of a church blasting prerecorded music, the muslim call to prayer, a TV at full volume, motorcycles passing by, women walking on the dusty roads with yellow buckets on their heads and roosters calling—all at the same time. These sounds converged, amplified by their newness, into a symphony of chaos.

Even eating was confusing.

We were at a restaurant and Moshi asked if I wanted chai tea. I thought I said “I’ll have coffee,” in English, and a few minutes later, the waiter came back with a cup of chai tea and then he emptied a packet of coffee into it. I just drank the bizarre tea/coffee combination thinking “yuck!” We were putting a lot of weird things into our bodies.

Dust had filled our pores, so we headed to our hotel for a much needed shower. Afterwards, we met up with Yasinta, who was going to be with us for the rest of the trip as our translator. We walked with her around the town and noticed babies in the arms of some young girls.

I used to want to grow up really fast, but now after being here, I’ve decided that I don’t ever want to get older. Being a kid is way more fun. Here, girls can be married off by their parents at my age as a way of paying off debts. Yasinta told us that a wife can cost two cows or even in some tribes only 40 litres of beer. Personally I think that I’m worth more than 40 litres of beer.

She also told us about this man from the Masai tribe who had 45 wives. How could someone have 45 wives? I can’t even get one boyfriend! It’s the richer men who have more wives because they can support all of the families. Each wife has at least two children, so if you have four wives, that would be eight kids. So, the man with 45 wives would have more than 100 kids! I sort of understand that someone could really love two people at the same time but 45?

Moshi himself had a wife named Isa, two kids, and a modest house—a simple room in the front with cement walls, a couch, a TV, and a fridge. There was another room in the back where the family slept. Most houses in any given village were made of clay, with cement being much rarer. Zoe and I would often be invited for dinner and eat on the floor with his family, but I always brought a few things from the market, and people at the market were always trying to get us to spend money.

Pretty much everything is sold outside on the street and people just walk around carrying the items on their heads and yelling to get your attention. There are no fixed prices. You have to barter. Communication is hard and people can be a little pushy but we figured out how to just ignore it.

Zoe was living a unique experience, but she was able to just watch and take it all in. I think she saw things that would forever change her view of the world. When she returned home, she had to sift through all that. We were able to laugh at ourselves and each other, and she hardly ever complained.