Honeybees are greatly affected by the annual rainfall and temperature of an area, and the dry season was brutal for the ones in Iyoli.

It’s been growing increasingly drier over the past decade due to climate change, and the bees need water to dilute honey and cool the hive during hot weather. If water is nearby, they can spend more time gathering nectar and less time collecting water. There was no water and only six bee box hives had survived out of the twelve that Zoe and I saw in the previous year.

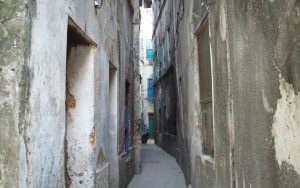

Last year, I took pictures of hundreds of people standing around filling their buckets from a well that was no longer providing water. Not a drop of water. Their backup water source was over 5km away at the Babu riverbed, and even that was dry.

The Iyoli well was built in 1973, and though it technically still had water, it had collapsed, probably because the casing had sunk. It wasn’t until recently that digging teams placed casings all the way down a well, a fact that made me happy that Moshi was there to ensure that the Cheku well construction had gone so well. More importantly, these old casings were also made of metal and not PVC, so they were prone to rust, and they were weighed down by waterlogged rocks. Gradually, all of the casings that were placed between 1960 and 1990 had begun to collapse, leaving those wells unusable.

The well was providing no water and the bees needed water.

But life went on. Each evening, the men got together and drank black coffee. Even though coffee costs pennies, the villagers didn’t always have enough, so when tourists came through, they would often sit together over a cup of coffee and talk—with the help of a translator. For less than $5, a tourist could pay for the entire group to have a cup. From beneath the stars, we talked about the drying fields and the disappearing bees while the cicadas sang their songs.

The people asked that I not forget them, and I knew I couldn’t just walk away without doing something.